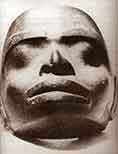

Black people were in Florida long before the Seminole Indians, and this is supported by the discovery of over 200,000 ancient pyramids and huge mounds of Earth fashioned like cones, animals, and geometric designs stretching from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, and from the Mississippi River to the Appalachian Mountains. These structures were built by the woolly-haired Black Native American people better known as the Mound Builders, who were the indigenous Inhabitants of North America and kin to the Olmecs of South America. On the left is an ancient Negroid basalt mask (1879) depicting what the Ancient American looked like before the arrival of Columbus, and on the right is a Black Californian native.

Black people were in Florida long before the Seminole Indians, and this is supported by the discovery of over 200,000 ancient pyramids and huge mounds of Earth fashioned like cones, animals, and geometric designs stretching from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, and from the Mississippi River to the Appalachian Mountains. These structures were built by the woolly-haired Black Native American people better known as the Mound Builders, who were the indigenous Inhabitants of North America and kin to the Olmecs of South America. On the left is an ancient Negroid basalt mask (1879) depicting what the Ancient American looked like before the arrival of Columbus, and on the right is a Black Californian native.

This movement of Afrikans would have taken place during Pangaea, “a period when the Afrikan and American continents were joined together” as indicated by the similarity of tropical plants, animals, geographic traits, and their shapes fitting together like a piece of a puzzle. This was before the continental drifts separated the landmasses into the 7 major continents, namely Afrika, North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Australia and Antarctica.

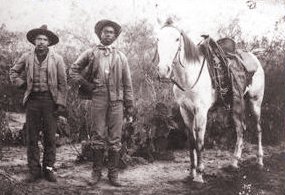

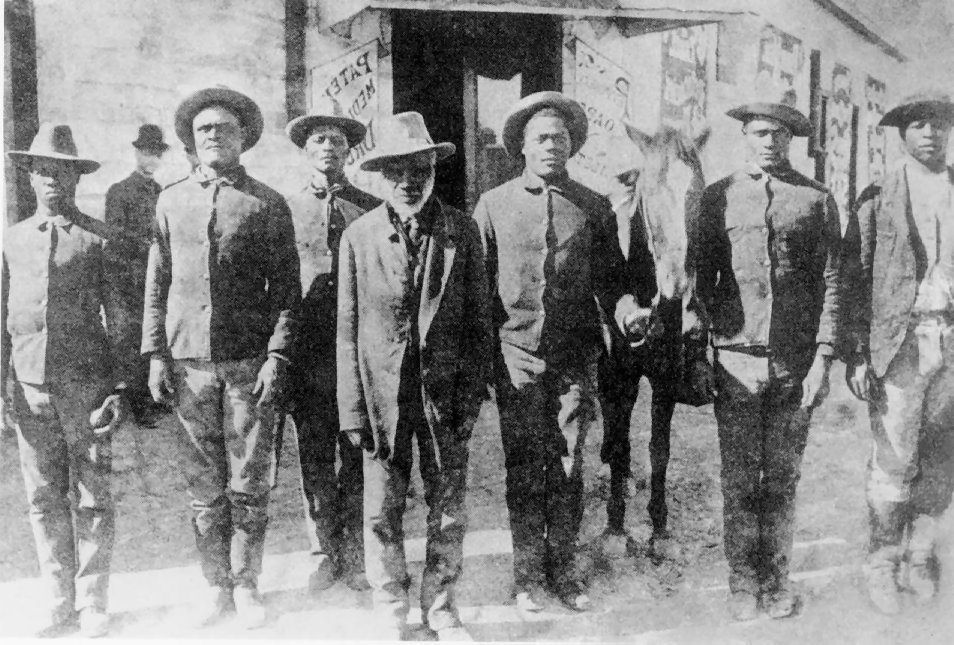

These Black Mound Builders were the Washitaw-Muurs or Ouachita – Moors, and many were huge as attested by their ancient skeletons, measuring between 7 to 8 feet. The only other living people on Earth with such a massive physique were the Massai of Afrika. On the left are some Mississippi Mound builders, the true khalifians.

These Black Mound Builders were the Washitaw-Muurs or Ouachita – Moors, and many were huge as attested by their ancient skeletons, measuring between 7 to 8 feet. The only other living people on Earth with such a massive physique were the Massai of Afrika. On the left are some Mississippi Mound builders, the true khalifians.

The term Mound Builders came about when the origin of these discovered monuments was deemed mysterious by European Americans, who wanted to believe that the Native Americans were too “uncivilized” and “barbaric” for such fine accomplishments. In reality this thriving Native American culture was common place in the Midwest and Southeast United States during the period when Europe was engulfed by the Dark Ages.

Columbus was therefore not technically incorrect when he called these people "Indians", because the word India comes from Indi which means Black, as in India ink, hindu and Indigo, the darkest colour in the colour spectrum.

Columbus was therefore not technically incorrect when he called these people "Indians", because the word India comes from Indi which means Black, as in India ink, hindu and Indigo, the darkest colour in the colour spectrum.

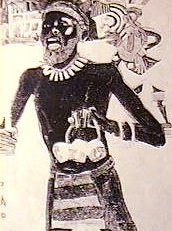

Here is a Black Californian native holding a bow and arrow, left during the period when California was ruled by a Black Amazon Queen. On the right is a Black Cherokee.

Included within the Ancient Native Black Nations of America before and after Columbus were:

• The Washitaw of the Louisiana/Midwest

• The Yamasee of the South East

• The Iroquois

• The Cherokee Indians

• The Blackfoot Indians

• The Pequot and Mohegans of Connecticut

• The Black Californians (Calafians) (CAL in California literally means Black,

after the name of the Great Mother KALi / Queen KALifa)

• The Olmecs of Mexico

• The Darienite of Panama

This is a Nisenan Indian Man with his arrows to the right somewhere between 1850 to 1860. The Nisenan were a group of Native Americans and an Indigenous people of California from the Yuba River and American River watersheds in Northern California and the California Central Valley.

The Nisenan were among the Native cultures that were destroyed by the California Gold Rush.

The Spanish, who in the early part of that century controlled Florida, gave land to a group of Creek Indians with the intention of creating a buffer zone between themselves and the English settlers who were located in Georgia and the Carolinas. The Creeks were joined by other tribes over a period of time such as the Mikasukis and the Apalachicolas. On the left is Mikasuki Indian Doctor Tiger - Miami, Florida.

The Spanish, who in the early part of that century controlled Florida, gave land to a group of Creek Indians with the intention of creating a buffer zone between themselves and the English settlers who were located in Georgia and the Carolinas. The Creeks were joined by other tribes over a period of time such as the Mikasukis and the Apalachicolas. On the left is Mikasuki Indian Doctor Tiger - Miami, Florida.

In the meantime, the Spanish encouraged runaway Afrikan slaves to head south by promising a safe haven if they converted to Catholicism. This policy showed Spain’s general inclusion of Black Afrikans at the various heights of society, an action which would have stemmed from the 700 years of Moorish occupation of the Iberian Peninsula.

By the late 1600s, Afrikan slaves who had escaped Carolina plantations and evaded slave hunters through dangerous Indian country, gained their freedom by crossing St. Mary's River, which was an international border dividing Spanish and British colonial territory. When the first fugitive slaves from Charleston arrived in St. Augustine, Florida in 1687, they were given refuge and were also integrated into a unified, multiracial, multicultural, multilingual community, where the men worked as Cartwrights, jewellers, butchers, and innkeepers, while the women worked as cooks and laundresses.

Others became farmers, ranchers, cowboys, interpreters, hunters, small business owners, traders and warriors. Some lived short, violent lives as outlaws raiding plantations, recruiting extra Blacks, and trading in contraband.

Others became farmers, ranchers, cowboys, interpreters, hunters, small business owners, traders and warriors. Some lived short, violent lives as outlaws raiding plantations, recruiting extra Blacks, and trading in contraband.

In this new environment these Blacks showed the ability to adapt, to be creative and to survive. By 1738, these former slaves had formed the first free Black community in North America known as Gracia Real de Santo Teresa de Mose or in short, Fort Mose. This outpost was established to protect the capital of Spanish Florida which covered from the Gulf of Mexico to Georgia and South Carolina, but it was also to assist the Spanish in weakening the slave-based economy of the English settlers in the Carolinas.

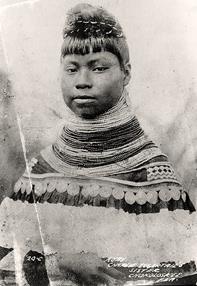

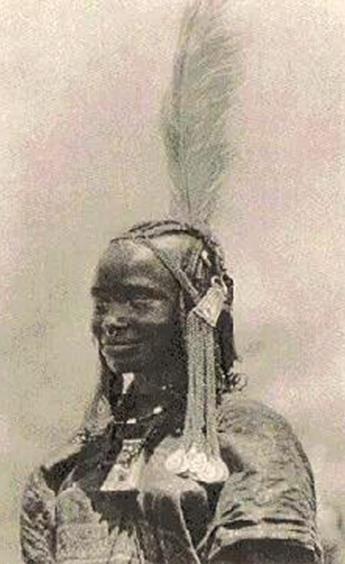

A West Afrikan Mandingo named Francisco Menéndez, who had escaped from the Carolinas with the help of Yammassee Indians, became captain of the Black Company at the St. Augustine garrisons, which was before the establishment of Fort Mose. He was also the captain of the garrison at Fort Mose, and the Spaniards had recognized him as the Cassique or chief of the community. Fort Mose was deserted around 1763 when Spain surrendered its colony to Britain, and some of the residents of the fort moved to Cuba. On the left is Ruby Tigertail, a Seminole / Yammassee woman. The Yammasee is the direct descendant of the Olmecs through the Washitaw Moors.

A West Afrikan Mandingo named Francisco Menéndez, who had escaped from the Carolinas with the help of Yammassee Indians, became captain of the Black Company at the St. Augustine garrisons, which was before the establishment of Fort Mose. He was also the captain of the garrison at Fort Mose, and the Spaniards had recognized him as the Cassique or chief of the community. Fort Mose was deserted around 1763 when Spain surrendered its colony to Britain, and some of the residents of the fort moved to Cuba. On the left is Ruby Tigertail, a Seminole / Yammassee woman. The Yammasee is the direct descendant of the Olmecs through the Washitaw Moors.

In 1994 Fort Mose was designated a National Historic Landmark and became the leading site on the Florida Black Heritage Trail. This provided a physical reminder about the people who risked everything, including their lives, in a valiant effort to obtain freedom.

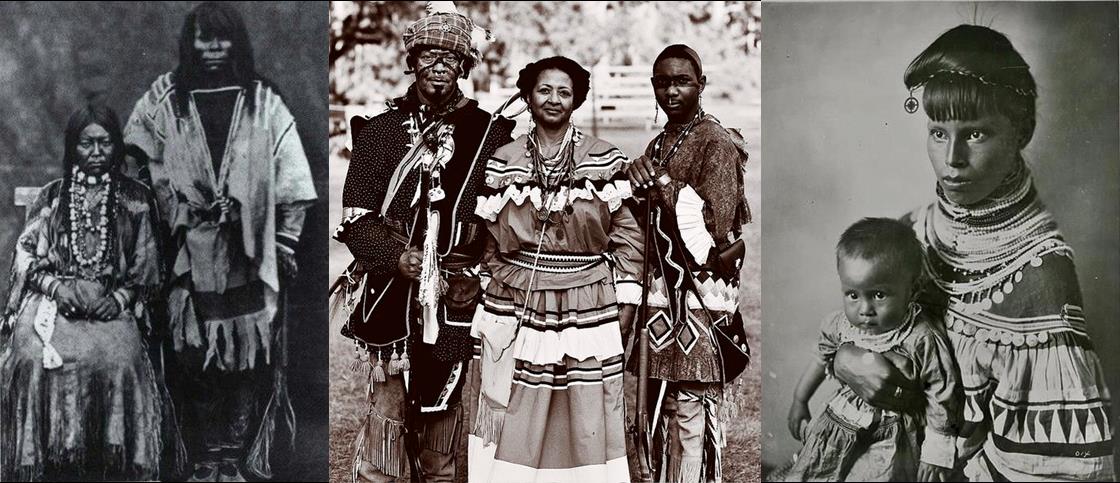

These Black Seminole Indians, also known as Indian Blacks, Black Muscogulges, Seminole freedmen and Maroons are the descendants of slaves or runaways from the plantations of South Carolina and Georgia who sought refuge in Spanish-controlled Florida, and lived among the Seminole Indians. They were closely associated with the Indians while maintaining a separate identity by preserving their own culture and traditions.

The remnants of the most resistant tribes like the Creek, Hitichi, Yammassee and Miccosukee Indians who were fighting the Europeans for centuries also followed, and by 1822 this group which numbered somewhere between 3,900 to 5,000, became known as the Seminoles, eventually breaking away from the main Creek tribe. The word Seminole comes from the Creek word "semino le" which means “runaway,” “emigrants who left the main body and settled elsewhere”, or “one who has camped out from the regular towns”. In Spanish the word may have been coined from the corrupted version of the word cimarrones.

The five so-called Civilized Tribes of the Southwest were the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and the Seminoles, who were considered the least civilized of the five Tribes because they did not harbour much prejudice against the Blacks. However, the U.S. Army kept harassing the Seminoles since they were the only tribe who was opposed to slavery, because they were aware that the Blacks who were being sold into slavery were a part of them, their distant cousins and relatives. Although they owned 800 slaves, it was not in the traditional sense of using the plantation style of bondage, since the Black Maroons were not subordinate to their chiefs. Consequently, the distinction between a runaway or slave became blurred and in due course vanished. The association between Blacks and Seminoles was one of affection and mutual respect, with intermarriage occurring between the two groups, so by 1907 no Seminole family was free of Black intermixing. Thousands of intermarriages took place between Blacks and Indians causing, in some cases, whole Indian tribes to disappear into the Black community. Blacks have similarly been absorbed into Indian tribes, which was largely due to the fact that until 1909 it was against the law to live in the Southeast and be a Native American. It was better to be passed off as Black and be a slave than to be uprooted and removed to Indian Territory.

The five so-called Civilized Tribes of the Southwest were the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and the Seminoles, who were considered the least civilized of the five Tribes because they did not harbour much prejudice against the Blacks. However, the U.S. Army kept harassing the Seminoles since they were the only tribe who was opposed to slavery, because they were aware that the Blacks who were being sold into slavery were a part of them, their distant cousins and relatives. Although they owned 800 slaves, it was not in the traditional sense of using the plantation style of bondage, since the Black Maroons were not subordinate to their chiefs. Consequently, the distinction between a runaway or slave became blurred and in due course vanished. The association between Blacks and Seminoles was one of affection and mutual respect, with intermarriage occurring between the two groups, so by 1907 no Seminole family was free of Black intermixing. Thousands of intermarriages took place between Blacks and Indians causing, in some cases, whole Indian tribes to disappear into the Black community. Blacks have similarly been absorbed into Indian tribes, which was largely due to the fact that until 1909 it was against the law to live in the Southeast and be a Native American. It was better to be passed off as Black and be a slave than to be uprooted and removed to Indian Territory.

The Southeast is where most of the inter-mixing between Blacks and natives took place, but it also occurred in the Northeast and the West where a mulatto mountain man named James Beckwourth who was a well-respected warrior known as Bloody Arm, married into the Crow Nation. The quality of life for ex-slaves improved as a result, and out of respect to the Indian chief, they paid a yearly tax of either corn or some other foodstuff for the common good, and in return for their allegiance, they were given the protection of the larger Seminole Indian community.

Seminoles, the descendants of Black slaves. To the right, a Seminole mother and child

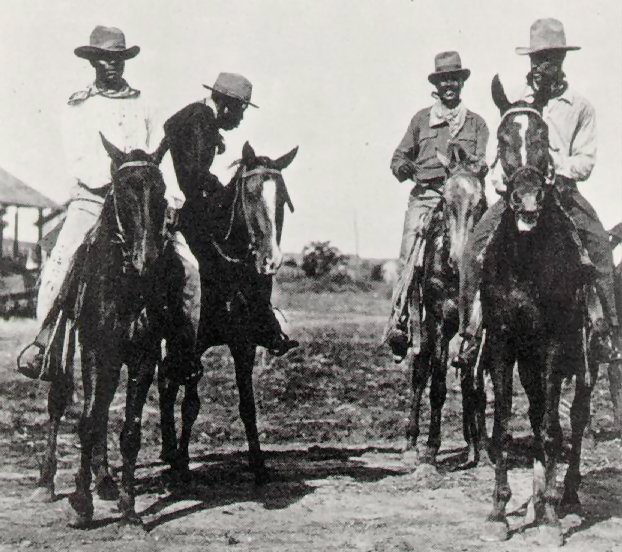

THE BLACK COWBOYS

A small number of Blacks, who had learnt to ride and manage the herds passed on their knowledge to the Seminole Villagers, teaching them horsemanship and herding skills as well as how to construct homes and speak both English and Spanish.

A small number of Blacks, who had learnt to ride and manage the herds passed on their knowledge to the Seminole Villagers, teaching them horsemanship and herding skills as well as how to construct homes and speak both English and Spanish.

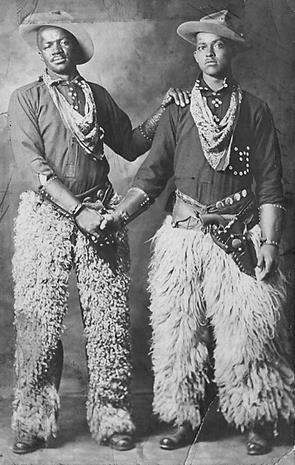

The first American cowboys [left-right] were definitely not the John Wayne or Jimmy Stewart type usually portrayed as white and tall in the saddle as highlighted in the movies, but were in fact Indians, Black men, or descendants of the Spanish Black slaves who were the first cowboys. Two famous early Florida Indians who raised cattle were Chief Billy Bowlegs and Chief Cowkeeper.

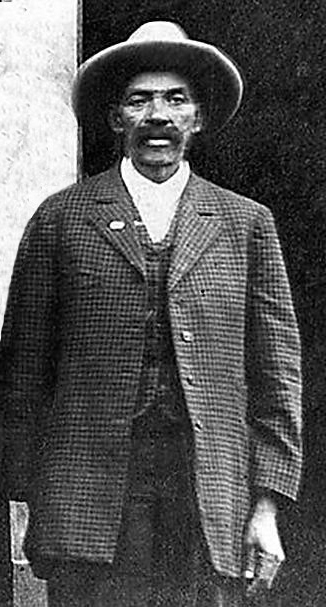

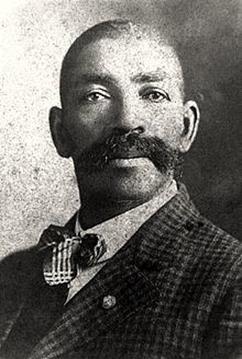

The toughest cowboy to ever live was a Black man named Bass Reeves, (1838 – 1910) (left) who was born a slave in Arkansas. He made friends with the Seminole and Creek Indians, learning to speak their language, and was also able to communicate very well in the languages of the other Five Civilized Tribes.

The toughest cowboy to ever live was a Black man named Bass Reeves, (1838 – 1910) (left) who was born a slave in Arkansas. He made friends with the Seminole and Creek Indians, learning to speak their language, and was also able to communicate very well in the languages of the other Five Civilized Tribes.

He took the time to familiarize himself with the tribes and their customs while sharpening his skills as an ambidextrous marksman, with the ability to fire a very accurate shot with his rifle or pistol using either hand.

Bass Reeves’ greatest strength was his expertise with firearms, as he was renowned for his ability to draw his guns at lightning fast speeds. He carried two big .45 calibre six-shooters with the handles facing forward, because he believed it was the fastest way to grip his guns. Numerous outlaws tried to out-draw him but 14 died in their vain attempts.

Standing at a towering 6 feet 2 inches, Bass Reeves was said to be blessed with supernatural strength. He rode a big white horse, wore a black hat, and handed out silver dollars as his calling card.

Bass Reeves was known as the greatest lawman of the Wild West, working mainly in the Arkansas and Oklahoma areas. With the help of his Native American assistant, Reeves was able to track down and apprehend a total of 3,000 criminals during his long career, killing 14 outlaws in self-defense. He achieved this through his skills and also because he feared no one. At times Reeves would use some sort of disguise as a means of getting close to the criminals before capturing them.

Bass Reeves therefore acquired the reputation as one of the most successful lawmen in the Indian Territory. His record of 3,000 arrests dwarfs those of better known old west lawmen such as Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp, and Wild Bill Hickok.

Contemporaries described Bass Reeves as a “lawman second to none”, a man who was “absolutely fearless”, and a “terror to outlaws and desperadoes”. He was said to be the “most feared U.S marshal that was ever heard of in that country”, and his nickname was the “Invincible Marshal”, the undisputed king of narrow escapes.

Contemporaries described Bass Reeves as a “lawman second to none”, a man who was “absolutely fearless”, and a “terror to outlaws and desperadoes”. He was said to be the “most feared U.S marshal that was ever heard of in that country”, and his nickname was the “Invincible Marshal”, the undisputed king of narrow escapes.

Upon his retirement in 1907, Bass Reeves became a city police officer in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

Upon his retirement in 1907, Bass Reeves became a city police officer in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

The legendary Bass Reeves was almost lost to history even though his deeds as a lawman greatly surpassed those of his white coequals.

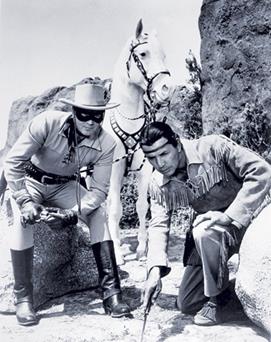

It is believed that Hollywood may have based the iconic character The Lone Ranger (right) on Bass Reeves’ legendary accomplishments, although he would have lived a far more dangerous and interesting life than what was gathered from the legends. His character however was played by a white actor - (Clayton Moore), which further supported the whitewashed depiction of the American west as another display of established racism at work in Hollywood movies and beyond.

For decades Hollywood has completely whitewashed the narrative of the Black cowboys of the Wild West, much like they did with Egypt and a string of other stories. In fact, many of the first settlers who were freed slaves travelled west and became the Black cowboys of the American frontier. In the 1870s and 1880s about 25 percent of the cowboys or one in every four cowboys on the Western Frontier were Black, yet their past has been whitewashed and ignored. The word “cowboy” is believed to have been coined as an insulting word to describe Black cowhands.

Cherokee Bill whose father was a Buffalo Soldier, was a notorious outlaw with a reputation and career that rivaled the reputation of Billy the Kid.

Black cowboys of the American frontier.

THE SEMINOLE WARS

The Blacks who lived among the Seminoles adopted the Indian way of living and dressing, and having mastered many language skills, spoke Creole, English, Spanish, and Indian (Muskogean) dialects. They also understood the ways of the white man since they lived on plantations, and this combination of skills made them invaluable to the Seminoles as interpreters, mediators and advisors. Their quest involved contact with settlers, traders, other Native Americans, government officials, the Spanish, British and American soldiers. Today their descendants can celebrate the persistence and perseverance of their ancestors who had suffered and survived deprivation, exploitation and destitution.

In due course the Blacks and Seminoles had established such strong communal ties that they merged forces and fought side by side to defend their land and freedom against their American adversaries who wanted to occupy Florida and prevent its use as a haven for run-away slaves. In contrast to the Anglo-American society, neither the Black Seminoles nor the Native American Indians aspired to subdue nature but to exist as part of the natural world. However, the U.S. government seemed determined to systematically eliminate the Native Americans and manipulate the descendants of the Black slaves, an imperialistic attitude which sanctioned the policies of the U.S. government to treat groups of people with less respect than they treated their own cattle.

General Andrew Jackson had arranged to eliminate the Seminole tribe, so he grouped the Creek tribes with U.S. soldiers to eradicate the Seminole resistance, initiating a war that lasted for decades stretching throughout Florida. The Army was faced with great opposition with the resistance of the Seminole who were guided by Chief Osceola. The First Seminole War (1817-1818) was started by the invasion of eastern Florida by U.S. army forces under the command of General Andrew Jackson, who destroyed Black and Indian towns, burnt Spanish forts, and routed the British. Finally Jackson captured Pensacola, and the Spanish ceded Florida to the United States in 1821. The Black Seminoles remained in Texas and moved to Oklahoma, Idaho, and mixed in with the Blackfeet, Comanche, Kiowa, Apache, Mandan, Omaha, Osage, Pawnee, Arikara, and the Wichita, their closest relatives.

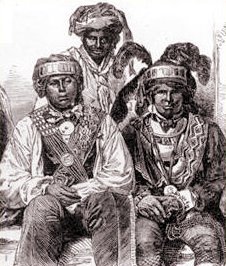

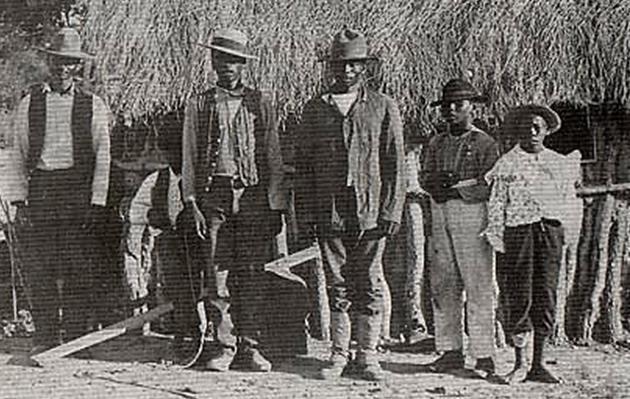

During the first Seminole War, Abraham, a former Black slave (left), fought against General Andrew Jackson's troops. Afterwards, Abraham recruited other Blacks into the tribe, and became an interpreter while also attaining the status of lawyer for

Chief Micanopy on his trip to Washington in 1826. He governed Peliklakaha, also known as Abraham's Old Town, and married the widow of Chief Billy Bowlegs. In the right photo from left to right are John Jumper, Abraham and Billy Bowlegs.

During the first Seminole War, Abraham, a former Black slave (left), fought against General Andrew Jackson's troops. Afterwards, Abraham recruited other Blacks into the tribe, and became an interpreter while also attaining the status of lawyer for

Chief Micanopy on his trip to Washington in 1826. He governed Peliklakaha, also known as Abraham's Old Town, and married the widow of Chief Billy Bowlegs. In the right photo from left to right are John Jumper, Abraham and Billy Bowlegs.

Twenty five miles north of the Gulf of Mexico up the Apalachicola River, more than 300 Blacks and Indians manned a fort called Negro Fort that the British had built for them. They fired at whatever ships came down the river until a single shot from an American ship hit the fort's ammunition dump, killing 270 of the 320 inside. When the war ended, the Black and Indian militia stayed.

Around 1823 some Seminole Indian leaders were pressured into moving to a reservation site in Florida and to return any runaway slaves that did not belong to them. Using the typical divide and rule tactic, the Indians were told that the Blacks did not care about them and only needed a place of safety from enslavement. Later, the 1830 Indian Removal Act passed by congress and authorized by President Jackson, decreed that the Indians be moved to the West, but the Black Seminoles resisted this relocation attempt by the land hungry American settlers, fearing that they would lose their homes, their independence, and their freedom.

The Blacks knew that if they assembled at one place along with their Indian allies waiting to be moved, they would be captured and sent back into slavery, so they took the lead in stirring up resistance to this removal, and joined the Seminoles in guerrilla warfare that incited the Second Seminole War (1835 -1842). Historians compared the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) to the Vietnam War where many Americans called the war un-winnable and immoral. Daily newspapers questioned why American boys were dying in a worthless piece of Florida swamp as the Seminole war grew into the longest and costliest of all American Indian wars. It was also the deadliest which cost the U.S. Government 30 million dollars with more than 2,000 regular soldiers and sailors lost. Although the North-South debate over slavery was in full swing at the outset of the Second Seminole War, the public at first was unaware of the connection between the slavery of Blacks and the removal of Indians from Florida, but the military was well aware of the connection.

Throughout the conflicts, Blacks were recognized for their aggressive military expertise which impressed both white opponents and Seminole leaders. Many warriors had come from the fiercest tribes of Afrika like the Igbo, Egba, Senegal and Ashanti, and as the war intensified, Blacks rapidly rose through the ranks, even wielding political clout within the tribe.

Throughout the conflicts, Blacks were recognized for their aggressive military expertise which impressed both white opponents and Seminole leaders. Many warriors had come from the fiercest tribes of Afrika like the Igbo, Egba, Senegal and Ashanti, and as the war intensified, Blacks rapidly rose through the ranks, even wielding political clout within the tribe.

The second war known as The Dade Massacre began on December 28, 1835 when a column of 108 soldiers led by Major Dade was massacred by Seminole warriors at the Dade Battle in Sumpter County. Soldiers hastily built a triangular barricade and held off the aggressors for nearly six hours until they were startled by the sound of pounding hooves. Fifty Black warriors on horseback swarmed the barricade, stabbing and axing the wounded, taunting them with cries of "What do you got to sell?" - A question soldiers often directed towards Blacks when they visited military posts. Only three whites survived. The horsemen most likely had heard the battle in the distance, and came galloping in to aid their comrades. The Seminoles were horrified by their allies with their to-the-death style of combat.

Four days later, the famous Seminole leader Osceola (pronounced Asi-Yaholo) (left) attacked a column of 750 men under General Duncan Clinch in the Battle of Withlacoochee in Citrus County with only 250 warriors. Osceola soundly defeated the soldiers, promising to fight the white invaders“till the last drop of Seminole blood has moistened the dust of my hunting ground”. The Seminole Nation fought slave trackers, other Indian tribes and the U.S. government in an attempt to keep their ancestral lands and farms intact.

Four days later, the famous Seminole leader Osceola (pronounced Asi-Yaholo) (left) attacked a column of 750 men under General Duncan Clinch in the Battle of Withlacoochee in Citrus County with only 250 warriors. Osceola soundly defeated the soldiers, promising to fight the white invaders“till the last drop of Seminole blood has moistened the dust of my hunting ground”. The Seminole Nation fought slave trackers, other Indian tribes and the U.S. government in an attempt to keep their ancestral lands and farms intact.

Greedy American settlers backed by the U.S. Army and the Federal Government, tried to forcibly remove and relocate the Native Americans along with any Black Seminoles from the Southeast section of the United States to Indian Territory (Oklahoma), in order to steal more land. General Jesup, frustrated by Osceola's continuing successes, resorted to the usual deception by luring Osceola, the great medicine man, and Chief Coacoochee (Wild Cat) into a trap under the guise of a peace meeting. When the Seminole leaders arrived at the negotiation site, they were promptly arrested and confined at Saint Augustine, then at Fort Moultrie at Charleston, South Carolina, where on January 30, 1838, Osceola contracted a fatal illness and died.

However, 19 of his fellow prisoners along with the courageous leader Wild Cat (right) and a Black Seminole named Gopher John (left) escaped and made their way to friends who assisted them by providing supplies. Wild Cat and Gopher John rode many miles together and developed a close friendship that lasted a lifetime.

However, 19 of his fellow prisoners along with the courageous leader Wild Cat (right) and a Black Seminole named Gopher John (left) escaped and made their way to friends who assisted them by providing supplies. Wild Cat and Gopher John rode many miles together and developed a close friendship that lasted a lifetime.

After a merciless and cruel roundup of Seminole families, the deadly journey began. Many tribal members did not have enough food or blankets, and as a result many died of starvation and disease while others were ambushed and killed by bandits who preyed on them. They were herded like cattle by the despised Bluecoats to Indian Territory on what is known as The Trail of Tears (1830), so named because survivors were not permitted to stop and bury their dead as hundreds of men, women and children were marched to their deaths. The Army however, was powerless to remove all the Maroons and Seminoles from Florida, because many of them hid in the thick vegetation of the Everglades. One such fierce warrior, a Black Seminole named Billy Bowlegs (Alligator Chief), led the tribe in the Second (1835-1842) and Third (1855-1858) Seminole wars.

The second war turned out to be a War of Independence for the Blacks. Some authorities even declared that this was the time when the Blacks emerged as a distinct social group, because they shared the experience of running away, resisting slavery, and fighting for their freedom. It was evident especially to the outside world, that they possessed the skills and intellect to survive on their own and to create self-sufficient communities.

The Third Seminole War started when a party of army engineers and surveyors working in the Great Cypress Swamp, stole crops and destroyed banana trees belonging to Bowlegs' band, and when confronted did not offer any apology or compensation. Bowlegs led his warriors in a series of raids on settlers, trappers, and traders.

Being close to starvation, Chief Billy Bowlegs (left) and his warriors hid in the swamps during the day, and carried out raids at night. This continued for several years because Bowlegs knew that life in the Indian Territory would have been less secure for Afrikan-Indians. Eventually, Bowlegs and some of his members, in exchange for small cash outlays, agreed to emigrate west, where he took 33 warriors with 80 women and children (about 165 altogether), to the Indian Territory (Oklahoma) on May 7, 1858. Relentless U.S. military raids and their bloodhounds reduced the Seminole population to between 200 and 300, but shortly afterwards, Colonel Loomis, commander of the forces in Florida, announced an end to all hostilities, since the U.S. government had abandoned efforts to remove all the Seminoles.

Being close to starvation, Chief Billy Bowlegs (left) and his warriors hid in the swamps during the day, and carried out raids at night. This continued for several years because Bowlegs knew that life in the Indian Territory would have been less secure for Afrikan-Indians. Eventually, Bowlegs and some of his members, in exchange for small cash outlays, agreed to emigrate west, where he took 33 warriors with 80 women and children (about 165 altogether), to the Indian Territory (Oklahoma) on May 7, 1858. Relentless U.S. military raids and their bloodhounds reduced the Seminole population to between 200 and 300, but shortly afterwards, Colonel Loomis, commander of the forces in Florida, announced an end to all hostilities, since the U.S. government had abandoned efforts to remove all the Seminoles.

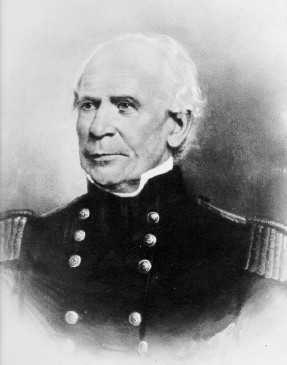

Again Blacks proved to be courageous fighters, serving in important roles as advisers, spies and intermediaries. Their influence on the Seminole Indian chiefs prompted General Thomas S. Jesup (right), to say, “this you may be assured is a Negro and not an Indian War”. To end the long, bloody and costly war, Jesup resorted to opportunism, granting freedom to the Blacks if they would go west as part of the Seminole Nation. However, once settled in Indian Territory (1841-1850), the Black Seminoles and the Seminole Indians faced another common enemy, the Creeks who were intent on enslaving the Black Seminoles and integrating the Seminole Indians into their community, but Wild Cat, the leader of the Seminole Indians and Gopher John, the leader of the Black Seminoles, resisted this domination. Wild Cat did not want his power diminished by the Creek chiefs, so he planned to form a confederation with other south-western Indians of which he would be the leader.

Again Blacks proved to be courageous fighters, serving in important roles as advisers, spies and intermediaries. Their influence on the Seminole Indian chiefs prompted General Thomas S. Jesup (right), to say, “this you may be assured is a Negro and not an Indian War”. To end the long, bloody and costly war, Jesup resorted to opportunism, granting freedom to the Blacks if they would go west as part of the Seminole Nation. However, once settled in Indian Territory (1841-1850), the Black Seminoles and the Seminole Indians faced another common enemy, the Creeks who were intent on enslaving the Black Seminoles and integrating the Seminole Indians into their community, but Wild Cat, the leader of the Seminole Indians and Gopher John, the leader of the Black Seminoles, resisted this domination. Wild Cat did not want his power diminished by the Creek chiefs, so he planned to form a confederation with other south-western Indians of which he would be the leader.

Gopher John and his group of Black Seminoles were more concerned about acquiring land where they would be safe from Creek slave hunters, but the kidnapping of Black Seminoles by the Creeks and white slave hunters became so prevalent, that Gopher John was forced to find ways to leave the territory. The Black Seminoles became upset when the U.S. attorney general in 1849 decided that Black Seminoles were still slaves, but the final straw came when the whites demanded that Black Seminoles, who were living in separate towns, must surrender their guns. Gopher John went to Washington to negotiate a special removal policy for his people, but since nothing came out of these efforts, he was left with no other choice but to join Wild Cat's plan to relocate to Mexico where slavery had been abolished since 1829. Many Black Seminoles escaped to the Bahamas after the First and Second Seminole Wars, but others, along with their Native American allies, were forcibly relocated to Oklahoma.

Some of the Afrikan-American Indians took the opportunity offered by Wild Cat, a Seminole Indian leader, to flee to Mexico in order to escape the pursuit of slave hunters, slave traders and the military. So in 1850, under the leadership of

Wild Cat and Gopher John, more than 300 Seminole Indians, Black Seminoles and Kickapoo Indians, set out for Mexico on a nine month journey to the border. The Mexican government, which desperately needed people to patrol the Texas-Coahuila border against the Comanche and Apache raiders and looters, promised citizenship to the migrants in exchange for protecting the northern border. They also provided the Seminoles with a joint grant of land at the juncture of Río San Rodrigo and Río San Antonio.

So one of the requirements for the migrants was that the men serve as border patrol to protect the towns against raids by the Comanche and Lipan Indians, an area in which the Black Seminoles again proved to be exceptional soldiers, gaining the reputation of being faithful troops. These Blacks drew on survival skills learnt while in the Florida wilderness, and adapted these skills to the harsh and barren terrain of the Mexican borderlands. As youths they learnt to ride, hunt, track, trap and shoot, becoming legendary frontiersmen. Some even served as soldiers in the Mexican Army, gaining a reputation for being tough and daring.

On entering Mexico in July 1850, John Horse said, “when we came fleeing slavery, Mexico was a land of freedom, and the Mexicans spread out their arms to us. The Black Seminoles eventually settled in Nacimiento where some of their descendants known as the Indios Mascogos still live to this day. The Seminole Indians settled nearby in Muzquiz. The Blacks put the food subsidies, tools for farming and building materials given to them to effective use, and soon had a flourishing agricultural community. A school and church were also established.

In Mexico, Gopher John was given the name Juan Caballo or John Horse, because he was very good with horses, but he became very famous after joining the Mexican Army and fighting against Maximillian's troops. John Horse was so brave that he was made colonel and later became known as El Colonel Juan Caballo. The Mexican Army gave him a silver-mounted saddle with a gold-plated pummel in the shape of a horse's head which he used whenever he rode his favourite horse. Eventually the Black Seminoles became tired of this role, especially after being summoned to engage in the civil and foreign conflicts that overwhelmed Mexico in the early 1860s, so at the end of the Civil War in the United States, the Black Seminoles looked forward to returning there. But external and internal pressures throughout the 1860s divided the Mascogos into three groups in Mexico; at Parras, Nacimiento, and Matamoros, with a group led by Elijah Daniels across the border in Texas.

By this time more white settlers had moved to the Southwest using the Overland Trail to cross from Texas into New Mexico, Arizona and California, bringing them into conflict with south-western Indian tribes like the Comanches and Apaches who were also relocated from their traditional hunting grounds to reservations in the New Mexico Territory. So in retaliation, they raided white settlements, stole livestock and horses, and destroyed property. Army personnel at frontier bases in Texas were not in a position to prevent these raids, because they lacked the necessary manpower to guard the unstable Texan border and track down or confront the fast-moving Indians, so what they needed were experienced fighters who knew the rugged terrain of the borderlands, understood the ways of the Indians, and could speak the border language which was (Mexican) / Spanglish -a mixture of English and Spanish.

BLACK INDIAN SCOUTS/ BUFFALO SOLDIERS

The Black Seminoles having lived in the border country for more than twenty years knew the land and the Indian groups that lived in or came into the area. These Seminole Negroes, with the reputation of being fearless fighters, were experts in frontier and hand to hand combat, so in 1870 the United States Army entered into negotiations with John Kibbetts, the leader of the group at Nacimiento, to employ Black Seminoles as Indian scouts and fighters in West Texas.

John Kibbetts was commissioned a sergeant at Fort Duncan where ten Black Seminoles enlisted as privates. This detachment of Seminole Negro Indian Scouts formed the 9th Cavalry's M Company. The assembling of the 9th Cavalry took place in New Orleans, Louisiana, during August and September of 1866. The soldiers spent the winter organizing and training before they were sent to San Antonio, Texas, in April 1867.

John Kibbetts was commissioned a sergeant at Fort Duncan where ten Black Seminoles enlisted as privates. This detachment of Seminole Negro Indian Scouts formed the 9th Cavalry's M Company. The assembling of the 9th Cavalry took place in New Orleans, Louisiana, during August and September of 1866. The soldiers spent the winter organizing and training before they were sent to San Antonio, Texas, in April 1867.

The soldiers included two regiments of the all Black cavalry, the 9th and 10th cavalries, which were formed after Congress passed legislation in 1866 allowing Afrikan Americans to enlist in the country’s regular peacetime military. Their main tasks were to help control the Native Americans of the Plains, capture cattle rustlers and thieves, and to protect settlers, railroad crews, wagon trains, and stagecoaches along the Western front.

The Black Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry regiment of the U.S. Army were based in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and were commanded by Colonel Benjamin Grierson.

The Comanche, who fought in the Indian Wars, were the first to call the Black Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry "Buffalo Soldiers" in 1871, a nickname conferred upon them based on the animal they revered most, the buffalo, because of the soldiers' woolly hair that resembled the buffalo, in addition to the army’s fierce fighting ability and toughness in battle, as this greatly impressed the Native Americans. It is believed that the nickname may also have been bestowed upon the "Buffalo Soldiers" based on the fact that they usually wore long coats made of buffalo skin during the harsh winters on the Plains.

Buffalo Soldiers.

After being promised that they could return to their former homes in the Indian Territory, many of the Afrikan American Seminole Indians opted to return to Texas. So on July 4, 1870, these Afrikan Americans and their families crossed the Rio Grande into Texas and established temporary camps on Elm Creek near the fort on military reservations, while awaiting clearance to the North, but top level government officials in charge of that task began to treat the matter as a low priority.

In 1871, Elijah Daniels' band and the Matamoros faction arrived at Fort Duncan, increasing the number of Black Seminole Scouts by eighteen. They worked to protect the borders and were promised salaries, rations, and living quarters for their families at the forts where they were stationed as recompense for their services. They were also guaranteed their own land in Texas or in the Indian Territory at the end of their service as scouts.

After the 1870s, the scouts' numbers were further strengthened by American freedmen, Mexican Blacks, and Blacks from the regular army. It took two years to find a commanding officer who could manage the Seminole-Negro Indian Scouts and gain their respect. That officer was Lieutenant John L. Bullis, a Quaker who commanded the United States Coloured Troops during the Civil War. John Bullis' fighting skills and religious background helped to establish a closeness with the scouts that resulted in him receiving invitations to perform marriages and baptisms in their Indian villages.

From 1873 to 1881 under the command of Lieutenant John Bullis, the Black scouts went on twenty-six expeditions and were engaged in twelve or more documented battles without suffering a single loss or incurring a serious injury even when greatly outnumbered, a credit to the Black Seminoles' skills and superior marksmanship. Unlike the soldiers, they could also live off half rations indefinitely. On a trail they were the best shots from the saddle and were capable of finding water and food that others had missed. They could also pickup trails from up to three weeks old, and even stay on a trail for months at a time. In one extraordinary act of tracking, Lt. Bullis and 39 scouts trailed Mescalero Apache raiders for 34 days over 1,260 miles. Many of these culprits incorrectly thought they had escaped from these scouts.

The Black Seminole Scouts were the best desert fighters and fighters in the history of the United States Army.

Famed for their bravery, four of the Black Seminole scouts were awarded the Medal of Honour in the 1870s for gallantry in action during the Indian wars.

Adam Paine was awarded the Medal of Honour for gallantry in action on the Staked Plains. John Ward, Pompey Factor and Isaac Payne were awarded the Medal for rescuing their commander, Lieutenant John Bullis. The trio rode in under enemy fire, and Ward pulled John Bullis up onto his horse before riding away to safety.

As usual, government officials had lied to the Negro Indians again, since the U.S. failed to honour its commitment and began denying responsibility for the safety and welfare of the group in spite of the numerous appeals by the scouts and the officers who supported their requests. Originally, the army classified the maroons as Indians and indicated that the group could be settled on Indian land, but questions soon arose from Indian agents concerning the ethnicity of the group. Near the end of their service to the government, Chief John Horse of the Seminole Negroes asked that their treaty be honoured, but the War Department claimed there was no copy of it therefore no land could legally be granted to them because they were not ethnic Indians.

BLACK SEMINOLE SCOUTS/ BUFFALO SOLDIERS.

(Left) Fay July and William Shields (1890), served the army for over 20 years. (Middle) Renty Grayson and wife Mary. (Right) Buffalo Soldiers.

TRUE NATIVE AMERICAN - MOOR.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs would not honour these claims either, claiming that they were not entitled to lands granted to real Indians. To make matters worse, registration for Seminole Indian reservation lands was closed in 1866, making the Black Seminole-Negroes in Texas and Mexico ineligible for any Indian Reservation lands, therefore the Black Seminoles never owned land anywhere after they left Florida.

There has been an ongoing debate among Seminoles with Afrikan ancestry and Seminoles with Native American ancestry regarding the legitimacy of the Black Seminoles. These arguments have reached crisis proportions as families are split along racial lines. Blacks Seminoles have been voted out of tribal councils and can no longer participate fully as Seminoles, while some have completely lost their rights in the Seminole nation. Strangely enough, the Indians who have mixed with European or Asian blood have no problem being accepted by the Native community, but Blacks on the other hand, find it a lot more difficult to obtain that same acceptance even though many of their descendants fought alongside them against the white man, and many Black ancestors walked the “Trail of Tears” with the Indians, still they are not accepted. This is mainly due to the general American prejudice, discrimination and governmental indifference against Black people who remain oppressed and disenfranchised.

BUFFALO SOLDIERS OF THE TENTH CALVARY WITH APACHE SCOUTS, 1885.

In 1879, Black Cherokees petitioned for full citizenship in the Cherokee Nation, declaring, "It is our country. There we were born and reared. There are our homes. There are our wives and children, whom we love as dearly as though we were born with red, instead of Black skins". Citizenship was granted. This is Gloria Hendry a Black Cherokee / Seminole Indian.

In 1879, Black Cherokees petitioned for full citizenship in the Cherokee Nation, declaring, "It is our country. There we were born and reared. There are our homes. There are our wives and children, whom we love as dearly as though we were born with red, instead of Black skins". Citizenship was granted. This is Gloria Hendry a Black Cherokee / Seminole Indian.

However, no amount of gallantry won the Black Seminoles the land they were promised under the treaties signed by General Zachary Taylor and President James Polk. By the 1880s the number of enlisted scouts was cut back, and an ungrateful army reduced their rations, but in spite of these setbacks, they continued to live on the Fort Clark military post under unsafe and often destitute conditions.

Buffalo Soldiers from the 10th Calvary, 1894.

After the Indian wars ended in the 1890s, the Buffalo Soldiers went on to fight in Cuba in the 1898 Spanish-American War, and also participated in General John J.Pershing’s 1916-1917 hunt for Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa.

Despite proving their military worth time and again, the Black soldiers continued to experience racial discrimination.

Buffalo Soldiers who took part in the Spanish American War and helped to free Cuba.

As the Indian wars declined, the scouts were transferred to custodial and constabulary positions before the detachment was finally disbanded in 1914, at which point the maroons at Fort Clark and their dependents who numbered between 200 and 300, were told to leave the post they had been living in for more than a generation. Bitterly disillusioned, many of the scouts left for Mexico in 1914, never to return, where the Seminoles and Maroons once again found liberty and a sense of community across the Mexican border. In the Mexican state of Coahuila where most of the Black Seminoles presently remain to this day, these Maroons or Mascogos, as they were called in Spanish, were able to acquire property, crops, and livestock. Others went to nearby Brackettville, where the Seminole Indian Scout Cemetery is located, and some tried to stay on at Fort Clark and Fort Duncan, but without any rations, some of them resorted to killing stray cattle for food, and as a result, local citizens often distrusted and resented the Black Seminole.

Black Seminoles in their village along Las Moras Creek close to Fort Clark, circa 1890.

The descendants of the Maroons or the Black Seminole community who live in West Texas today continue to use the name Seminole to set themselves apart from other Blacks, and to emphasize the pride they had in their unique history of having run away and resisted slavery. They are still proud to declare themselves Native Americans. It was a long, hard road for the Black Seminoles and Maroons who had to overcome the persecution of the Spanish, the English, slavery, disease, the abuse by the United States Army, the Trail of Tears, starvation, bounty hunters, other hostile Indian tribes, and the unfavourable conditions of the Indian Territory of Oklahoma, yet through all of this, they managed to survive. The fact that they were not completely eradicated and still have descendants living today is testimony to their tenacity, bravery, and enduring strength of spirit.

The descendants who live in Coahuila, Mexico, refer to themselves as

Indios Mascogos, and in Oklahoma as Freedmen, for similar reasons. The experience of the Black Seminoles was similar to other maroon societies that prospered throughout the Americas before slavery was abolished, and because they were in constant fear of being recaptured, they defended their freedom by developing extraordinary skills in guerrilla warfare. They were proactive in finding ways to survive economically in new environments, and were also skilled in their interaction with Native Americans. Leaders emerged from their communities who were savvy at understanding and negotiating with whites, but most importantly, all of these maroon communities borrowed, combined and integrated elements of their experiences into their own Afrikan heritage.

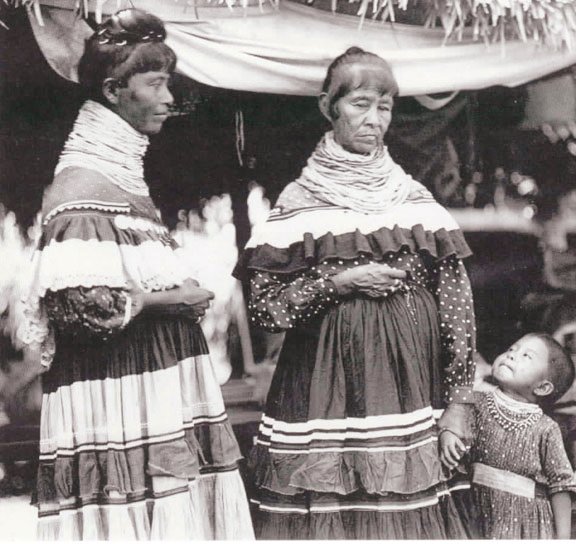

From the 1920's onward, development exploded in Southern Florida causing the Seminoles to lose hunting land to tourists and settlers. They were gradually forced into the wage labour economy where they become agricultural workers, attracting tourists with their exciting and colourful patchwork clothing. Here are two Black Seminole Maroon Women.

From the 1920's onward, development exploded in Southern Florida causing the Seminoles to lose hunting land to tourists and settlers. They were gradually forced into the wage labour economy where they become agricultural workers, attracting tourists with their exciting and colourful patchwork clothing. Here are two Black Seminole Maroon Women.

As usual, many historians have ignored the important cultural contributions of the Black and Indian relationships, since the background of European colonial imperialism has corrupted the intellect by “representing both Afrikans and Indians as uncivilized peoples without any histories, who have not contributed anything to the world”. Books, movies and television shows have never spread their story, and as result, only a few people have heard or even know of their existence, or the mark the Seminole-Negro Indian Scouts left on the frontier west.

This is Diana Fletcher a Seminole school teacher at the schools built for Black native Americans.

© John Moore - Barbados, W.I. (March 2000) ©. All rights reserved.